Note: the CD I listened to was the 1998 reissue.

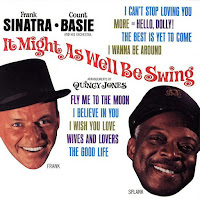

Originally released about two years prior you my birth, this CD represents the collaboration of a 'perfect storm' of musicians: Sinatra, Count Basie, and Quincy Jones. This brief (27'26") album has everything you could ask for from a Sinatra disc, including leading off with my all-time favorite Sinatra tune: Fly Me To The Moon (In Other Words). It's all a master class in swinging, arranging, phrasing, performing, and, as mentioned below, musical economy: saying more by playing less. Firmly in the pocket. Hold your hat, turn up the volume and dig.

|

| Billboard, August 8, 1964, p. 52 |

This reissue didn't include the original album's liner notes, an interview with Quincy Jones on the back cover, so I've included them below.

Peak on the US Billboard Top 200 chart: #13

Tracks: Lemme try to rank 'em

- Fly Me To The Moon (In Other Words)

- I Believe In You

- The Best Is Yet To Come

- The Good Life

- More (Theme from Mondo Cane)

- I Wish You Love

- Wives And Lovers

- I Wanna Be Around

- Hello, Dolly!

- I Can't Stop Loving You

Previously revisited for the blog:

Sinatra Sings Cole Porter (2003)

The Capitol Years (1990)

Sinatra at the Sands (1966)

|

| For more information on the brief life of the CD longbox, go visit The Legend of the Longbox. |

Liner notes:

A Conversation With Mr. Jones

Prior to the recording of this album, arranger and conductor Quincy Jones set up a temporary private studio within the Sinatra offices at Warner Bros. Studios, Burbank, California. At the studio Jones wrote his arrangements: at the same time, Sinatra acted in and, for the first time, directed his new film, "None But the Brave." To prepare for the recording sessions, Jones (whom Sinatra nicknamed "Q") often worked late into the night framing his arrangements, occasionally sleeping at the Sinatra offices.

In the following conversation, Jones discussed the atmosphere at the sessions, the preparations for them, and the musical results. He began by talking about the audiences at the Basie-Sinatra sessions.

It's very helpful to have an audience to play off, particularly when they're responsive and attentive, as the audiences at these sessions were. The atmosphere was very informal, but it was relaxed rather than chaotic. I know Basic's band plays better with an audience, and I think Frank does too. But a remarkable thing about Frank is that he is able to tune them out. When he starts singing, he forgets they're there. He has a fantastic power of concentration. And of course, you really do have to concentrate at a record session because after you get out of there, the music you've made is on record forever.

A lot of work goes into a rehearsal because you're so cognizant that a record is a permanent thing. A lot of sweat is involved. A lot of soul, too, but a lot of work. Each session-and there are usually three for most albums-is only three hours long. I don't think many people realize how serious those hours are. Not that we don't also enjoy ourselves when things are working right-as they did on these dates.

How did the idea of getting Count Basie, Frank Sinatra and you together begin?

It was like a chain letter. I was thrilled because I'd always wanted to work with Frank and I know Basic had wanted to do another album with him after their "Basie-Sinatra" set on Reprise. What happened was that Reprise called and said Sinatra would be back in California from Hawaii, where he'd been shooting on location for "None But the Brave," on May 27th. I said that wouldn't give us much time if we were to record on June 8th or 9th and that I'd like to get with Frank as soon as possible to talk over the songs with him. The next thing I knew I was in Hawaii, and that was beautiful. Frank had said, "Come on over here," and so I picked up Bill Miller, his accompanist, in California and we were off.

How did you two work in Hawaii?

I don't know how Frank finds the time, but within one hour after I arrived in Hawaii (I was-there some six or seven days altogether), we were straight. It was a Sunday, and we met in the home in which Frank was staying. Bill Miller and I came into the room. After being fueled by some "gasoline" (the Jack Daniels kind), we were at the piano. Within an hour, we had all the routines worked out, the modulations, the tempos and the styles for each tune. There were no problems at all. Nothing but love from the beginning. Frank is so alert musically and so resilient that he's marvelous to work with. He was open to all suggestions, and he had some of his own too.

How did things go at the sessions themselves?

To begin with, the way Frank records makes it much easier to establish rapport. Instead of getting off in a kind of isolation booth, as many singers do in a studio, Frank stands in a small half-shell near the rhythm section. There everybody can see him, and he can feel directly what's going on around him. Again, at the dates, Frank was exceptionally aware of the best methods to use, the most comfortable way to do the songs. I remember that in "I Believe in You," for example, there was a little rhythm figure Frank wanted to insert in the bridge. And Basic's drummer, Sonny Payne, remarked at the time what a pleasure it was to work with so musical a singer and to work, moreover, with a man who, in a sense, was able to swing him.

What were some of the ways in which you adapted some of the songs? For example, one of the tunes was "I Can't Stop Loving You," which you arranged for Basie on his Reprise album, 'This Time By Basie." You won a Grammy from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences for that How'd you change it for this album?

We put an intriguing little bass figure underneath it, and we got the strings playing almost saxophone figures on it. They interpreted those patterns very well. I tried to notate it so that if would feel very loose.

Most of the songs come from fairly well known original versions.

Yes, we did take songs which had been identified with very specialized kinds of backgrounds, like Jack Jones' "Wives and Lovers." But we had to transmute them because when you're working with a combination as unique as that of Basie and Sinatra, you have to discard all superfluities and get to the bones of a song before you start building it again. I think we accomplished that. In the case of "Wives and Lovers," for instance, we changed the 3/4 waltz tempo in which it was originally written into 4/4 time. And we also added a kind of mesmeric shuffle beat. "Fly Me To The Moon" had also originally been written as a waltz and later become famous as a bossa nova. For this date, we translated it into a swinging 4/4 time.

How did you select the tunes that would best fit the string-augmented band which was present for two of the three sessions?

It was a difficult challenge. I tried to select those tunes which had the kind of harmonic elements which would be particularly heightened by the colors we can get with strings. "Good Life," for example, and "More." In the latter, the strings seemed especially apt to enhance the groove we were getting.

What is your approach in writing for the Basie band?

I've been with this Basie family for a while now, and I think I understand what they really groove with. Once I can bring an arrangement up to that point-where it's comfortable and right for them-they just take it from there. They add a distinctive personality to the score, a personality of a quality you can never get out of a studio band. For one thing, there is no way any studio band can achieve the cohesiveness of a group that's been together a long time. Take the Basie sax section. It's the best reed section I've heard anywhere in the world -live or on records. One of the reasons for their superiority is that each man in it is an excellent musician, and the other reason is that they've been together for ten years. They are just like a family, and cannot be equalled by anybody.

Another basic factor in the Basie band's personality is that rhythm section. Its beat is so fundamental that, in a paradoxical sense, it's timeless. It seems to go back to the very foundation of what rhythm is. There's Basie himself and Freddie Green and Sonny Payne, whom the musicians call "Magoo." That's another index of the family byplay in the band. Everybody has a nickname. Basie is "Splank," Buddy Catlett is "Bumblebee," and Freddie Green is "Pepper."

Basie, of course, is renowned for playing as few notes as possible, and that seems to be particularly in evidence in this set.

The word "economy" is an understatement when referring to Basie. During one of the tunes, Frank said, "Give me the pitch, Basie" And Basie hit one staccato note-"splank!"-and it was all there. It's not only economy; it's authority. When Basie plays, there's no waste motion just as there are no wasted notes. He knows exactly what's needed-and how to do it.

You also brought in a few added musicians.

One was Harry Edison, also known as "Sportin' Life" and "Sweets" He's been featured on Frank's dates with Nelson Riddle for years. Edison has a particular quality. In fact, only Joe Newman can also do the kind of thing "Sweets" does. They play their trumpet like a saxophone. Where another trumpeter would play with too much animation or with too wide a range, "Sweets" can say a great deal with just a few notes because he can bend and shake those notes and make them contain so much substance.

You added other brass as well - Al Porcino on trumpet and Ken Shroyer on bass trombone.

We did that because there are times when a singer who is building a groove and building a picture on a song might have to stop and wait until the blood comes back into the trumpet player's lips. By having men in reserve, we don't have to disturb a singer's groove. And we also added percussion-Emil Richards, and, of course, the string section. I should note that the strings contained the loveliest cellist I have ever seen in a string section.

Finally, what distinguishes writing for Sinatra?

To begin with, he is so personal a singer. Nobody can imitate him. Sammy Davis, Jr. is one of his closest friends and yet Frank is the one imitation Sammy really can't do. He can do the mannerisms, but he cannot imitate that sound. Secondly, Frank is unusually sensitive. He is so flexible musically that he fits easily into every situation. And when he has an idea he wants to incorporate, he is able to immediately absorb the whole musical context surrounding that idea. He utilizes every asset he finds, and he's an expert at eliminating stumbling blocks. Both he and Basic have this remarkable ability to eliminate the negative. In "I Wish You Love," for instance, we had a pickup which tipped off the tempo. Frank just omitted it. starting off with the voice. A very natural thing to do and one that worked out perfectly. And there is also his rhythmic sense and inventiveness. He can stretch out a little further even in a set rhythmic figure. And he's not constricted by the melody as it was written. He bends it so that invariably it fits flawlessly into what's going on in the background. So far as I can put the essence of Frank into words, I'd say that he just makes everything work. He makes everything fit, and that's exactly what happened on these sessions.

No comments:

Post a Comment